Life in Fukuoka: On society and culture shock

Disclaimer: This post is ripe with generalizations based on my observations as a foreigner in Fukuoka. Note that when I say “the Japanese”, I know not everyone here abides by these principles. And more than anything, I’m referring to the people we interact with day-to-day in Fukuoka, which is located near the country-side and is much less diverse than Tokyo. Please enjoy!

Low tide canals in Fukuoka at sunset during the winter

Low tide canals in Fukuoka at sunset during the winter

We’re just passed our second month here and officially halfway through our stint in Japan. It’s been interesting to look back and reflect on how our perception of Fukuoka and Japan in general has changed since first arriving starry-eyed. Unsurprisingly, living and attempting to integrate into Japanese society generates different situations than visiting for a short period of time would. For someone like me who finds immense joy in noticing and analyzing all the details, it’s been amusing to say the least.

Dare I say we’ve officially surpassed tourist status? Restaurant owners and coffee shop keepers are starting to recognize us. Staff at our neighbourhood sake bar recounted seeing us walking around the area. We’re getting better at navigating the local bus lines of this canal city wherein we’re starting to feel the comforts and familiarity of Home.

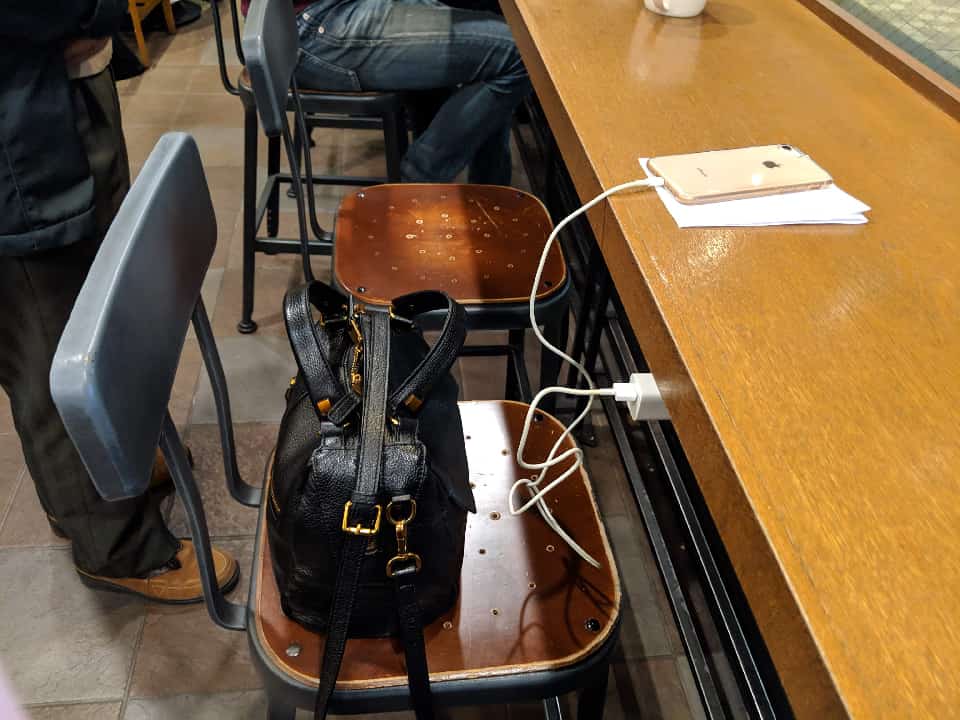

While discovering Fukuoka as a city has been relatively straightforward, the cultural landscape has been more difficult to scale. We’re realizing every day the extreme differences and lack of overlap between Japan and Canada & the US. For starters, as I’m sitting here typing at a busy Starbucks, the lady next to me has left her phone charging and her purse unattended for about 15 minutes now.

Gone in 60 seconds if this was in San Francisco

Gone in 60 seconds if this was in San Francisco

By far the biggest difference and shock is the ubiquity of common courtesy in Japanese society. The hyper-awareness of when one might be inconveniencing someone else is instilled deeply. I feel this could explain many peculiarities someone might come across as a tourist, such as why public areas from shops to the streets are often kept tidy and clean, and why service people always appear so polite and attentive. On top of that, the Japanese concept of hospitality, Omotenashi, in which one attempts to anticipate someone else’s needs before it’s shown or even realized by the person themselves, further distinguishes an already idiosyncratic society.

This can be felt in every day life. The bus driver waits for each new passenger to sit down before starting the bus up again. A restaurant worker will walk you out to the streets to bow goodbye. A supermarket cashier will name every item they are scanning and recite the price to you almost melodically. A fellow patron might notice that you’re trying to find a seat for two and willingly move without being asked or even leave the shop so you can sit together.

Then, it gets more intense. We’ve noticed that hosts at a very fancy restaurant will stay in the bowing position on the streets while covertly stealing glances to see if the diners have left their field of vision (In Japanese culture, there is a hierarchy when it comes to who should give the last bow). Multiple people have apologized to us for their poor level of English. (How I would respond if my Japanese was half decent: ‘Um hello? We are in Japan and our Japanese is poor. We are sorry! We’re in your country! And if you’re speaking English at all, we absolutely think that’s amazing!) If you go to a large department store like Bic Camera or Yodobashi, you might catch a worker awkwardly running without trying to seem like they’re running because their arms are clinging by their side. Chances are they are getting something for someone and they don’t want to keep them waiting too long since department stores in Japan are huge, but they also don’t want to cause alarm by running through a store frantically.

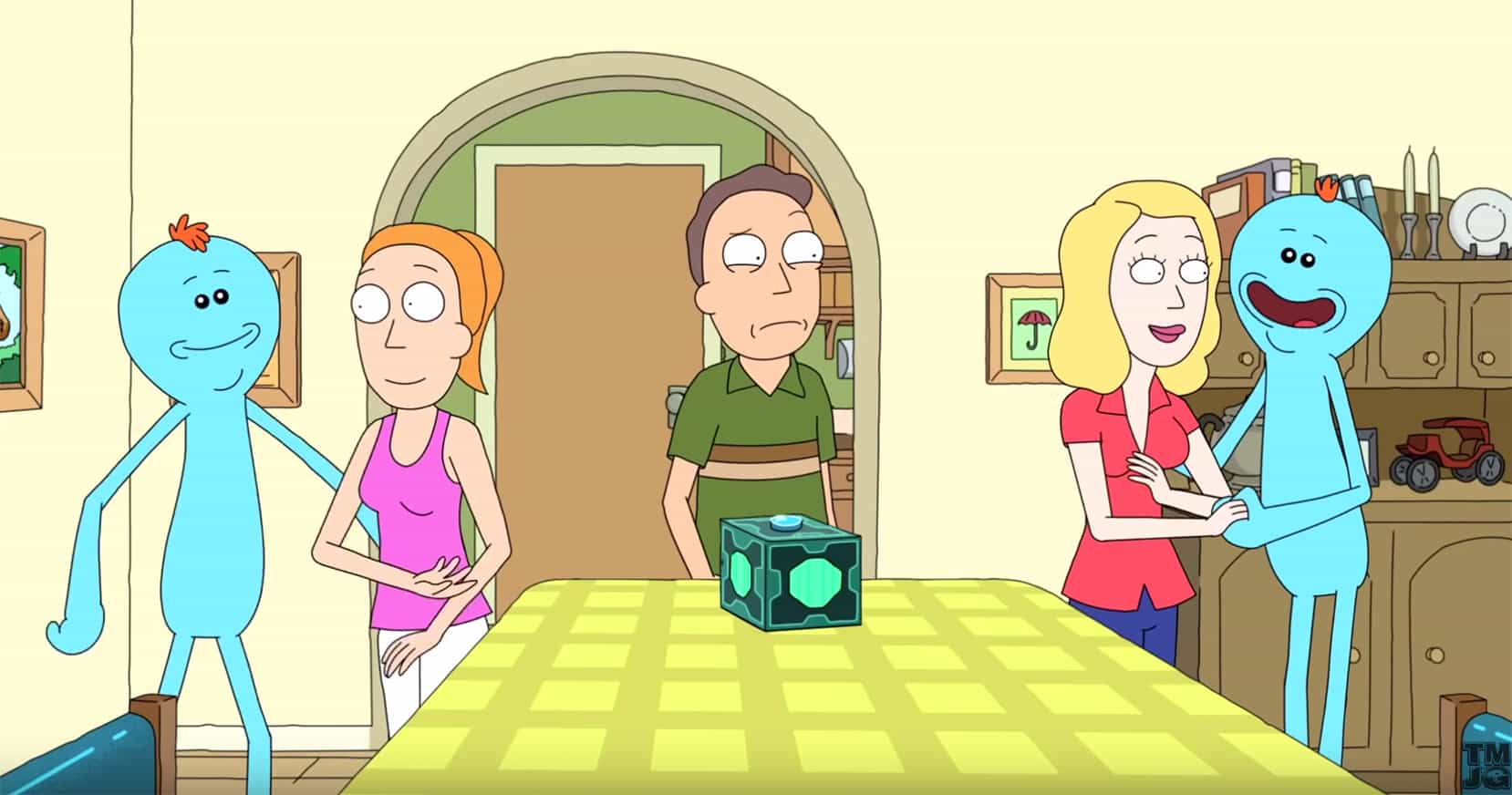

It seems that while the Japanese are heedful of inconveniencing others, sometimes they are self-sacrificial and will inconvenience themselves in order to keep you at ease. But to us foreigners, this usually results in an elevated level of awkwardness because we are unaware of how to navigate such a social situation. If you’ve ever seen the episode of Rick & Morty with the Meeseeks box, I sometimes wonder if the Meeseeks were inspired in any way by an exagerated version of the service-oriented Japanese. For those unaware of the episode, “Meeseeks[1] are creatures who are created to serve a singular purpose for which they will go to any length to fulfill […] If a Meeseeks is not given a purpose at the beginning of its existence it seems to default to taking the purpose of the Meeseeks before it” (credit).

Two Meeseeks summoned to help Beth and Summer with whatever they desire

Two Meeseeks summoned to help Beth and Summer with whatever they desire

Once, as we were leaving the Startup Cafe where we work out of, I casually asked one of the volunteers if they knew where else might be open to laptop workers during the day. He couldn’t think of a place and proceeded to summon 2 of his fellow volunteers. Together, they racked their brains for an uncomfortable number of minutes as Justin and I were awkwardly trying to convey that it’s not a big deal because we were aware there aren’t many places but figured it wouldn’t hurt to ask anyway. It took a while to abort the situation and we got some very unnecessarily deep apologetic bows on our way out.

We’ve adapted in some weird ways to this. Because our Japanese is still not very good, we often find ourselves struggling between wanting to ask about something but not wanting to accidentally trigger the relentless pursuit of a Japanese person. In other words, we might avoid asking a staff member for help because the amount of effort they will pour into finding the solution for us might not be worth the period of awkward broken communication. Sometimes we get anxious if we’re leaving a place and the shopkeeper who had been serving us is no where to be seen; we don’t want them to feel bad for missing the opportunity to say good bye! Sometimes after we leave a shop and we hear someone running, we get worried thinking we might have forgotten something. It’s very common to see shopkeepers and waiters chasing after a patron who left something at their shop– embarrassingly, it has happened to us twice!

Update (2019-04-19): Last week while we were visiting Kagoshima, a shopkeeper chased after me with a 1 yen coin (equivalent to about 1 U.S. penny) that I had apparently dropped when I was rummaging through my change purse to pay.

Another facet of this vigilance is that they can’t seem to bear delivering any sort of bad news. Oftentimes, we will walk into a restaurant that happens to be full or not accepting new diners. Instead of simply telling us the facts, they will say a lot of “sorry’s” while bowing their head apologetically and slowly pushing us out the front door.

They also have special vocabulary that exonerates them from giving any further information or excuse so as to “soften the blow”. The common one is “chotto” which can literally mean a million things depending on how you say it. This article explains it well; I still haven’t been able to wrap my head around it. The gist of it is depending on the context, it can mean anything from “a little” to “a lot”, from “wait a moment” to “can’t do it”. Notably, it can be used as a cop-out to say, hey I don’t really want to get into it and I want to save us both from discomfort so I’ll just say chotto, and the other person will understand and both people will move on. Conceptually, it’s a word that I would like to use on other people but would be very annoyed if someone used it on me.

There’s a lot that we still can’t quite figure out. When we think we have reasoned an unfamiliar habit or reaction, we discover something contradictory. For instance, in Japan, the notion of mottainai is very strong. In short, it represents an ideal of not wasting anything and not taking more than you need of anything. It ties into a lot of behaviour. We’ve heard anecdotes on how the Japanese seldom throw things out or replace them even if it’s broken. Children are taught from a young age not to waste food and to finish every grain of rice. This recent Economist segment describes an ongoing radical recycling movement. Public buses and a number of cars (at least the rental cars we’ve been getting) seem to run on an eco-friendly engine that shuts off when idling. Sounds great and environmentally conscious, yet Japanese consumption of single-use plastic is awful. We’ve experienced shopkeepers’ mindless excessive bagging of purchased goods, disposable wet towels wrapped in plastic served at numerous restaurants, single-day-use face masks which are worn by nearly everyone during winter, and a new plastic sleeve for covering your wet umbrella anytime you enter a shop or restaurant.

A common sight at supermarkets: individually wrapped vegetables

A common sight at supermarkets: individually wrapped vegetables

Update (2019-04-19): I’ve come to realize that this excessive use of plastic at the supermarket is in fact very much in line with their principles of not wasting. Wrapping perishable items in plastic prolongs the lifespan of the food, thereby reducing food waste both at home and at the supermarket. They have just chosen to not waste food over not creating plastic waste. Also, the 2016 discovery of this plastic-eating enzyme is a pretty neat and might explain why the Japanese bin-sorting system is so strict about PET plastic versus normal plastic!

Additionally, there is a strong notion of not disturbing or causing discomfort to others. Anyone who’s been to Japan will notice how quiet the subways are, even when they are absolutely packed. You could hear a pimple pop on a bus full of people during rush hour. They just don’t talk. However, when allergy season comes around, for some reason, is when this rule has its one exception. I now have confirmation that Asian men are the loudest sneezers in the world. I thought it was just my dad for the longest time. There is no effort to conceal the sneeze. It is as if all the noise they have pent-up is permitted to come out all at once and it is excusable, because, well, the entire country of Japan goes through allergy season together at the same time.

The Japanese are also relatively conservative people. They don’t dress in revealing clothes compared to the west and they can be profoundly shy. So shy that in most public (and even in some home) restrooms, the sound of streaming water will play to mask the sound of one’s peeing. You might think you could understand why performing a normal human function behind closed doors might make them feel uncomfortable until you learn that hot springs and public bathhouses in which patrons are expected to strip fully naked is pretty much a standard activity.

Lastly, while the archetype of anything Japanese is highly efficient and process-oriented, for some reason, there lacks a canonical side of the street to walk on. We are constantly startled when we’re walking on the sidewalks even though we are trying hard to be aware of our surroundings. If you want that Japanese “Mario Kart” experience, just walk on the sidewalks with bikers zooming by and pedestrians all over the place.

Yet there is somehow organization to all this chaos. There’s rarely honking and everyone seems to be able to manoeuvre whatever obstacles are in the way. We walk down this small side street all the time and it is shared by bikers, pedestrians, scooters and cars. The craziest part is that while it appears as a single lane road, it is actually bi-directional. I stood there for a few minutes and it didn’t take long to capture the following photos to show varying states of occupancy:

Pedestrians taking up the whole street

Pedestrians taking up the whole street

A car coming through with pedestrians in the way

A car coming through with pedestrians in the way

Three cars trying to navigate around each other

Three cars trying to navigate around each other

In fairness, there are tons of great perks from having a society in which 99% of members are courteous, polite, and respectful. This is literally a fantasy world. When I was still living in San Francisco and I had a car, I often dreamt of a place where ‘courtesy re-park’ could be a thing– a concept in which anyone could re-park anyone else’s car if they just needed an inch or two more for parallel parking. I wouldn’t be the least bit surprised if this already happens in some Japanese towns.

Justin and I went to our first concert in Japan a few weeks ago to see a female hip hop duo, an electronic music producer and a ska band perform live. The venue was filled with young people dancing and drinking. There were noticeable differences with the way people act at concerts here. While I can report that even in Japan, people will push their way to the front, the difference is that they genuinely look ashamed and are bowing their heads apologetically to everyone they happen to pass by. I also noticed that there is way less obnoxiously loud singing and woo-ing or screaming to take advantage of the lulls, just to be potentially noticed by the band. But to me, the biggest difference was the behaviour when all the performers came out to take a group photo with the audience at the end of the show. I’ve been in plenty of these, or rather I have tried to be but because I am short and have no desire to be in the front row of any show, I usually just accept that I’ll be hidden among a sea of arms in the air. To illustrate my point, here are some random concert selfies I found on the internet:

creditGloria Gaynor

creditGloria Gaynor

creditSelena Gomez

creditSelena Gomez

creditSome random group from Morocco

creditSome random group from Morocco

Now here’s the photo from the concert we went to:

creditClick here for a bigger version!

creditClick here for a bigger version!

I’m actually in it! Thank you Japanese people and your aversion to being in the way of others. Also, notice that the only people raising their hands are the ones on the sides, presumably because they know they wouldn’t be in anyone’s way!

At the end of the day, every bit of the experience of being in Japan is enjoyable to us, even the frustrating bits. They are fun to decipher and when we ask our Japanese friends for more context, it often ends in mutual shock that the other culture doesn’t do a particular thing the same way. Personally, these culture shocks are my favourite parts of any travel I do. It forces us to question why we do things a certain way and challenges what we perceive as normal. Ultimately, it helps us understand ourselves and the world better, plus it creates lots of interesting stories to share!

[1] Unsurprisingly, in the Japanese dub for Rick and Morty, the Meeseeks are voiced by a woman.